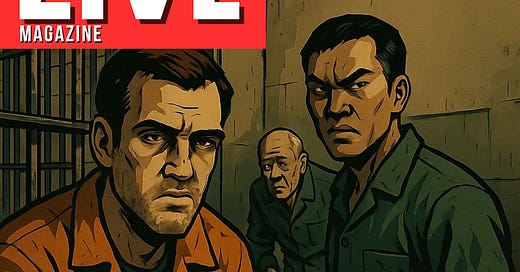

I was doing a stint in a Tokyo prison on a trumped-up fraud charge. I was on assignment, there to cover organised crime. I told them from the start I was the wrong guy for the job. They smelt me a mile away. My trial was set for a fortnight and I was yet to find legal representation. I was assured this would be provided to me in time but I didn’t trust anyone I interacted with. I didn’t trust the bail judge who said I had nothing to worry about when I appeared on my arrest, only to find myself continuously on remand.

“The wheels of justice in Japan are notoriously slow,” my cellmate told me over a game of canasta one rainy afternoon.

“I’ve been here three months and still no date,” I complained.

“Toru-san! Come here,” he yelled out to a fellow inmate in the mess hall. An elderly inmate in rag-tag prison greens strolled over, holding on to the seats to assist him.

Daichi spoke to him in Japanese briefly and then returned to me.

“Been here seventy years,” he said. “Still no trial.”

“You’re lying!” I said.

“You calling me a liar?!” Daichi stood in anger.

“You’re freaking me out that’s all!” I explained. “How long have you been here for anyway?” I asked. This seemed to calm him down.

“I’ve never left, feels like I was born here,” he explained. He had a hardened look, one that betrayed his young features. Like he had seen a thing or two beyond his twenty-eight years.

“Who told you I was twenty-eight?” he asked. I never said anything.

“No one,” I said. “Or maybe the guard, I don’t know. I forgot.”

“I’m much older.”

“You don’t look it,” I said.

“You see Toru-san over there?” he asked me, pointing to the man who had just joined us. I nodded.

“We were arrested together, on the same charge,” he explained.

“What charge was that?”

“War crimes,” he said.

“Hard to believe he had committed any war crimes in his state,” I replied. He ignored my comment.

“There was a jurisdiction change when we were rounded up by the Americans. The country had disbanded its courts and they left us languishing in our cells until a new regime could put us on trial,” he said. “That was seventy years ago.”

I dropped my cards and looked up at him.

“How old are you?” I asked.

“Lights out!” the guards yelled as they entered the mess hall, swinging their batons and motioning us to enter the cell halls and into our rooms for lock up.

I sat there on the top bunk staring up at the ceiling, waiting for the final guard to pass before silence fell on the prison. I knew I could speak to Daichi all night after that. The last of the footsteps passed, and I seized my opportunity.

“What did you mean by what you said earlier today?” I asked.

“I meant everything that I said,” he replied.

“So, you’re like ninety years old?” I asked.

“Ninety-three.”

“Why do you look twenty-eight?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said.

We lay there in silence for a while. I thought he fell asleep. Then he began to speak once more.

“I don’t mind indefinite detention as punishment. I was the commander of the Yokohama camp. It was spring. We were half full. Toru was rounding up a fresh wave of Chinese prisoners of war. We had a sneak attack from an infantryman. A defector. Trespassing from the woods that surrounded the camp. The prisoners all saw him coming with his rifle. He was an expert shot. He took out both guards in our tower. We were vulnerable to an escape, and here he was, trying to break in. I don’t know if he was trying to liberate the place or if he was just losing his mind. He was in full uniform, which made us hesitate to fire on him. Eventually, he took out two more of my men with his pistol, and I had no choice. He made it to the fence and carved away at the barbed wire. He moved his body under the hole he had dug and commanded into the encampment. He marched over with a knife in his hand. A giant Bowie. I told my men to hold their fire. I raised my rifle. I yelled out that he was trespassing!”

Daichi was screaming the story at me from the bottom bunk. I heard the entire bedframe rattle as he acted out the motions of his memory.

“Shut up in there!” came the voices of our neighbours.

“He kept marching towards me, like he had this look of death in his eyes and all he wanted to do was to gut me. I yelled at him again to stop! He wouldn’t. Then he reached me close enough to say that the woods were culled for the prison. We had destroyed Mother Earth and all her fruits so that we could lock up people. We deserved death at the end of his blade…”

He was silent after that.

“So what did you do?” I asked him after a while.

“I gave him death.”

“You shot him?”

“In the leg, and then I had him hung and decapitated.”

I could hear Daichi start to cry.

“Seems excessive,” I said.

“The look of death when he lay in that box was gone, and he had an inner peace that haunts me to this day,” Daichi said between sniffles and tears.

I let him cry himself to sleep. I lay on my bunk, hoping my fate would not mirror his. I prayed that I would one day be released so that I could put pen to paper and tell the mysterious story of Daichi. The oldest known prisoner of World War Two. The forgotten prisoner. Even if he was lying to me, it was a hell of a story.

I wondered if my day would come.

I hoped that my day would come.

“Daichi?” I asked when the tears subsided. He was breathing heavily, but I needed to know.

“Daichie?” I asked again. I got down from my bunk and began to shove his shoulders. He awoke in a fright.

“What?!” he yelled.

“Was that true?” I asked.

I could see in the moonlight as he lay himself back down to sleep.

“Go back to bed,” he said in an audible smirk.

“I need to know if that’s true,” I pressed.

He turned to me once more.

“It could be an old Japanese folk story,” he said. “Or my tears were real. If you choose not to believe, that is your battle,” he said. He rolled over away from me and, before long, was snoring away into the wall.

I climbed back onto my top bunk and thought of the trespasser. I thought about how stupid he was breaking into a prison.